TES news articles

G&T: ‘We must stretch all students, not a privileged few'

One senior leader on how her school is moving from a policy of ‘gifted and talented’ towards ‘stretch and challenge’ for all

Many years ago I taught a student – we’ll call him Josh – who was an all-round high achiever: strong in academics, an excellent sportsman, and engaged in the classroom. Lately, however, Josh had started to behave differently. When asked if anything was wrong, he explained he had received a letter from the school to let his parents know that he no longer met the criteria for the gifted and talented programme. “Aren’t I clever anymore?” Josh asked, with that typical teenage mix of genuine hurt concealed by a thin veneer of bravado. Unsurprisingly, it was a thought-provoking moment.

Josh did go on to achieve great things, but his reaction is just one reason that our school’s gifted and talented policy is now based on “stretch and challenge” for all students, not just the privileged few.

Privileged is an apt word to use, as evidence shows that higher-attaining students from poorer socio-economic backgrounds don’t make the same progress as their more affluent peers.

Our brains continue to develop and adapt well into adulthood; in adolescence, they are still being moulded. Ability is not genetically pre-determined, but malleable and environmentally dependent. Although prior attainment is a strong predictor of future attainment, it is far from infallible: we believe students should be set mastery goals appropriate for their current attainment rather than performance goals.

When students’ understanding of content and concepts is secure, they should be provided with expert models to emulate, and be given complex and open-ended tasks to challenge them. How is it possible for a student who is behind to catch up unless their work is challenging? All students should be working hard and should be supported to do so.

Gifted and talented for all

So, how do you develop an inclusive stretch and challenge policy for all?

Although we still have a gifted and talented register, teachers are asked, and expected, to focus on stretching all pupils in addition to those who have been identified as G&T.

We provide a rich curriculum including Latin and Classics for all our key stage 3 students. Additionally, opportunities for stretch and challenge need to extend beyond classroom walls. A recent visit to our partner college in Oxford saw our students being taken on a tour by Malala Yousafzai. In another current initiative, teachers are participating in a lecture series on topics they are passionate about: so far, we have heard about Victorian writers’ responses to social inequality and an overview of American history.

Our students go to the theatre, take part in formal debates, compete competitively in maths, science and a range of sports and help other students with learning difficulties. Our definition of gifted and talented recognises that all students have something to offer: we support each other to achieve our full potential.

We need to provide our students with a high-quality education, whether academic or vocational, which enables them to make a success of their lives.

That success can be difficult to define. Some studies suggest that a child’s emotional health is far more important to adult satisfaction levels than their performance in exams. Instead of encouraging competition, maybe we should empower our students to capitalise on their own aspirations, not those that are imposed upon them.

We continue, as always, to support and inspire our highest attainers to become the best they can be, and indeed all our learners to do the same, while maintaining the balance between excellence and fairness. Consistently high expectations for all is imperative: all our students have the right to an education that meets their needs. This way we all gain – not just the chosen few.

Julie Smith

04 June 2018

Please click HERE to read the article 'How can schools use research to better inform teaching practice?'

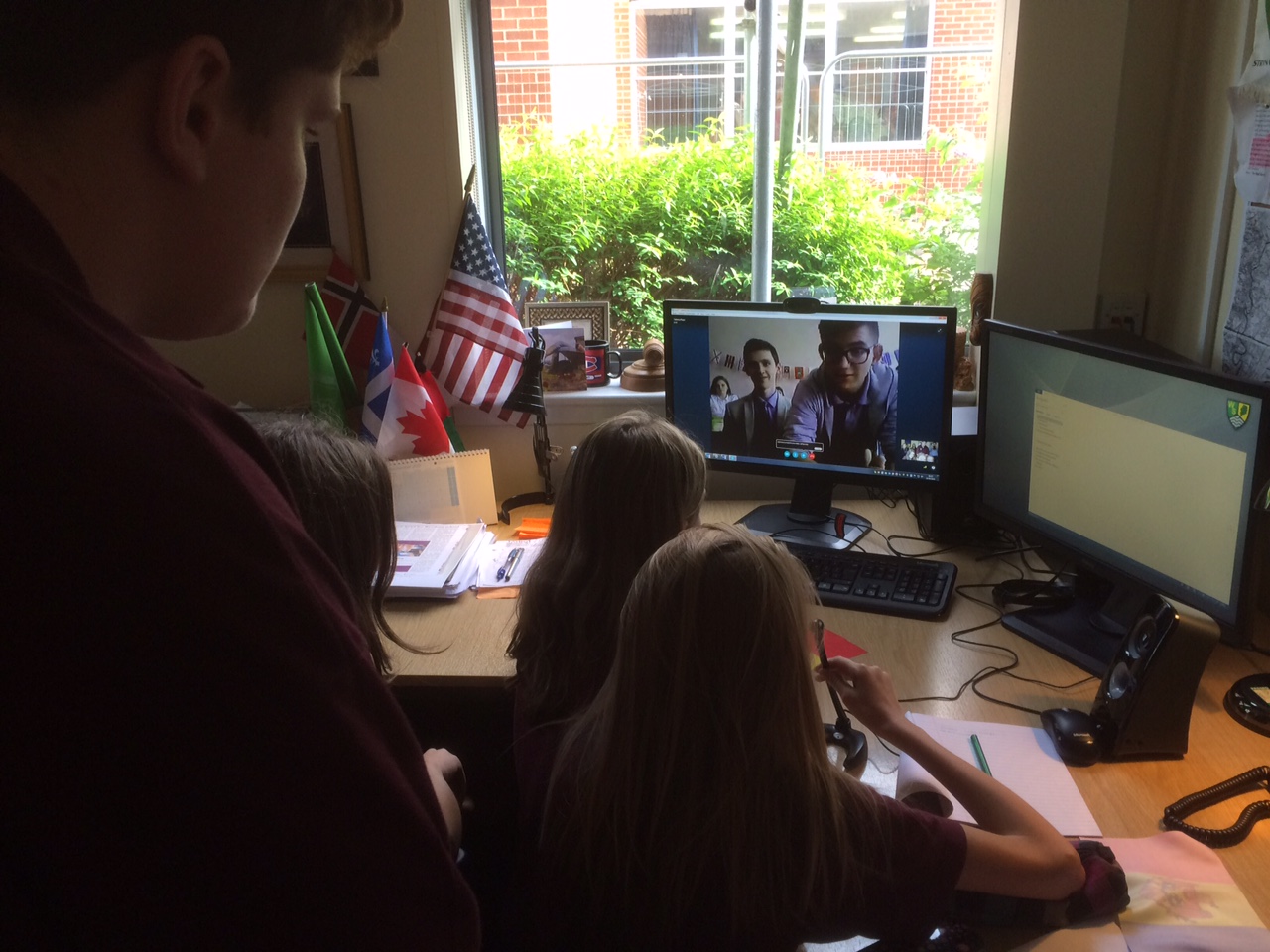

A Day in the life of.... Tatiana Popa - Moldova partner teaching 08 - 09 - 17

Please click HERE to read the full article.

‘Why I came to distrust differentiation’

This teacher has decided that differentiating students based on prior attainment puts limits on student aspiration and teacher expectation

A well-meaning, but misguided alteration to our school lesson plan template just before an Ofsted inspection was the beginning of the end for my relationship with differentiation.

A well-meaning, but misguided alteration to our school lesson plan template just before an Ofsted inspection was the beginning of the end for my relationship with differentiation.

The blank new lesson plan arrived in my inbox, neatly divided into three columns, one for "less able students", one for "the majority of students" and one for "more able students". As the lesson planning pro forma was introduced in a meeting, I sat silently, seething.

Who were we to judge what students could achieve before a lesson had even begun? And what did "less able" and "more able" mean anyway?

Dangers of differentiation

Labelling and notions of fixed ability are rife throughout our education system. It isn’t unusual for teachers to be encouraged to divide students into groups according to their prior attainment, and to provide "appropriate" work for their level. This practice of within-class ability grouping – fairly common in primary schools, but also used in the secondary sector – implies that students’ ability is a fixed entity.

Perhaps instead we should be exploring the notion that, given appropriate learning opportunities, all students can achieve, even if they may not all progress at the same rate?

The issue of self-esteem also seems critical to me: surely some students feel less valued if they feel they have been labelled as "low-ability"? The requirement of some schools that their teachers write every lesson objective according to "all, most, and some" creates, I believe, an opportunity for both teachers and students to lower their expectations.

And if activities are presented as being purely based on performance, then they are seen by pupils as a test of ability rather than an opportunity to learn. To meet task demands and avoid failure, students may rely on surface-level learning strategies, avoid challenges and give up easily.

Mastery breeds motivation

In contrast, mastery goals emphasise the challenge of learning, stressing the importance of continuous improvement. This can prove particularly motivating for students and promote student autonomy if students choose the focus of their goals based on precise teacher feedback.

As many of us know, the importance of teacher feedback, verbal as well as written, has been documented by the Education Endowment Foundation, and cited by John Hattie in his meta-analyses Visible Learning. The EEF comments that teacher feedback has a high average impact on student attainment, reminding us that schools should mark less, but mark better; we should set aside time for students to consider and respond to marking, and careless mistakes should be marked differently to errors in understanding.

Similarly, Hattie points out that feedback is one of the most powerful influences in student achievement, although he also warns us that giving feedback is complicated, and given incorrectly, can actually have the opposite effect.

Despite these complexities though, differentiating for current, rather than prior, attainment removes the potential for low expectations that "all, most, some" lesson objectives can create.

Ditching differentiation

Fortunately, our school is now beginning to take the more challenging and inclusive approach of differentiating for current attainment, "teaching to the top" and responding to students during the lesson as the need arises.

I find that sometimes challenges are anticipated, and sometimes students need help in unexpected ways. Developing positive relationships with students, as well as a clear understanding of their strengths and weaknesses, is so important, and this knowledge is far more in-depth and complex than simply basing our differentiation on a summative number filled in on a seating plan.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A studied lesson in recovery

In 14 months, our school went from good, to special measures, and back again. Personally, this led to a loss of confidence in the inspection system, professionally, (and thankfully only briefly), it damaged the reputation of the school, and as a staff, it led to a steep decline in morale in a workforce that had previously been full of pride.

In 14 months, our school went from good, to special measures, and back again. Personally, this led to a loss of confidence in the inspection system, professionally, (and thankfully only briefly), it damaged the reputation of the school, and as a staff, it led to a steep decline in morale in a workforce that had previously been full of pride.

The reasons our school ended up temporarily in special measures are somewhat mystifying, and partially due to the well-documented English GCSE fiasco of 2012. The inspection judgement seemed arbitrary, and driven by an opaque agenda that felt difficult to understand. Almost as soon as we were plunged into special measures, we were deemed to be out of it again, but the experience had inevitably taken its toll.

As teachers, we know that the Ofsted model of educational evaluation is essentially merely quality assurance. Previous to the fateful 2013 Ofsted inspection, levels of insecurity among the staff had already been heightened by the use of graded lesson observations, which were seen as an inevitable consequence of a low-trust accountability system. During the time that we were placed in measures, I was researching the impact of differing models of classroom observation for my M.Ed. In questionnaires and interviews, teachers expressed a sense of powerlessness about the observation process, and were concerned that something of the spirit of the school had been lost. They stated a preference for informal peer support and self-reflection as preferred approaches to improving their practice, and the perception that graded lesson observations were punitive was evident throughout their comments. Teachers referred to graded lesson observations as a box ticking exercise, and not a true reflection of normal classroom practice.

So, as a staff, how did we not derail entirely? How did we not just survive this turbulent era in the school’s history, but instead, find ourselves thriving?

One line manager tentatively suggested, ‘perhaps trust is the key’. The staff rallied, refusing to let the situation defeat them. There are now a multitude of ways that a culture of trust is being re-established in the school: the introduction of a democratic and distributed leadership model; a wider range of staff leading their own initiatives; staff ownership of their own CPD; greater links with other schools and professional bodies are to name but few. We were also lucky enough to be given supportive guidance from a fantastic HMI, who helped us define a clear sense of direction and ensured we never became complacent. One of the changes that epitomises our return to a culture of autonomy is the introduction of lesson study as a model of classroom observation.

Despite our experiences with Ofsted, we have always believed that every teacher can improve, and that lesson observation is a valuable form of professional development. Thankfully, it has now been proved that graded lesson observations are neither valid nor reliable. Instead, we are finding alternative ways of observing lessons and in doing so, we have reclaimed our professionalism. We have recently completed our first pilot of lesson study, in which a triad of teachers collaboratively plan, teach, observe and analyse learning and teaching in research lessons.

Findings have been interesting: one triad, looking at student resilience, avoided the current trend to address ‘growth mindset’ in schools through motivational posters and assemblies as it was felt this may be inadvertently misleading for students: whilst an absence of effort guarantees failure, ‘more effort’ is not necessarily a guarantee of success. Instead, the intervention was based on Martin and Marsh’s research into academic buoyancy, and the triad focussed their attention on the impact of teacher feedback. Findings were that, for these students, feedback was particularly effective when delivered verbally, although further questions were raised about ways to increase student self-efficacy. A further triad has examined the effect of setting personal targets for students, finding again that specific, verbal feedback directly related to assessment objectives seems to be more impactful than merely offering reassurance. Our final triad’s lesson study reiterated the importance of setting clear and specific goals, as they investigated using reflection points to aid student progress.

There are some interesting trends emerging from the initial pilot. The power of positive teacher-student interactions seems to be key: students who feel supported by their teachers appear less likely to be alienated and disengaged from their work; a sense of belonging seems to promote a sense of achievement. A further benefit of the process is the close focus on authentic student voice, putting students at the forefront of planning and reflection, and thereby ensuring the students have joint ownership of their learning. The collaborative nature of lesson study is popular with staff: it relies on teacher professionalism, and offers respectful challenge and support from peers.

The process of lesson study is not without its detractors, and we are not naïve enough to think that lesson study is ‘the’ answer. As an evaluative process, it is time-consuming, and in order to be carried out properly, it must be underpinned by theory and research. It is helpful that I am studying for a professional doctorate: my course is driven by practical research tasks, and gives me a good understanding of the complexity of educational issues, in addition to improving my research literacy so that I can support others who don’t necessarily have the time to engage with or assimilate the scale of reading that is required.

The beauty of the structure of the lesson study process is that it prioritises development over surveillance, and also contains an element of measuring effectiveness – there must be demonstrable impact on student progress and attainment, while ensuring teachers remain at the centre of the planning, teaching and evaluation process. We are using accessible summaries of research, such as the EEF’s toolkit, to ensure that we avoid poor proxies for learning, and we are focussing on teacher learning to improve teacher quality.

The issue of power has been paramount in enabling us to thrive: our current education system can feel stifling, and can discourage individual initiative by encouraging conformity and control. Undertaking research is a way that teachers can take increased responsibility for their actions: it is a method of returning teachers’ self-worth.

9th March 2017 at 00:00